When you are entering a new space (playing a new game, taking on a new business venture, etc.), what do you do to learn the area quickly and try to find an edge?

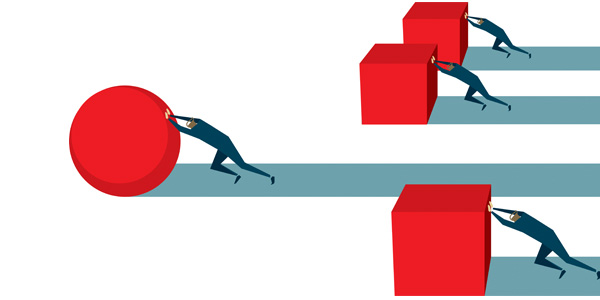

Thanks to Pat for the email, which hits on a key word that I believe is the most important component to finding an edge: quickly. More so than being right, being fast – and first – is the true key to finding an edge. Think about the differences in the competitive landscapes of things like early DFS/poker versus the games today, or building a stacked MLB roster pre- and post-Moneyball.

Whenever possible, be a big fish in a small pond. If you want to find an edge in whatever game you’re playing, first make sure you’ve chosen the right game. I use the word ‘game’ loosely here. To me, almost everything in life – certainly in competitive settings – is a game; there’s really no fundamental difference in how you should approach starting a business as compared to kicking your friends’ asses in Monopoly, for example. And being first to the scene is the easiest way to reduce competition.

Second, learn the rules. This sounds simplistic – and it can be – but you’d be surprised how many people don’t truly grasp the rules. Even in true games with clearly defined rules, so many people make sub-optimal decisions. I was playing Connect 4 recently with someone who was genuinely trying to win but didn’t care about going first or second. I’ve chosen to no longer speak to this person.

In games with less-defined rules, like business, you need to work to figure out the rules and how to beat them. In less efficient markets, of which I believe much of the business world falls, you can get by simply looking for and exploiting edges in these obvious areas (see my 40 counterintuitive tips to business).

And finally, make up your own rules whenever possible, which goes back to being first; a game might have defined rules, but the games within the game are ever-changing and able to be manipulated. Billy Beane was participating in the same broad game as every other MLB team, but chose to win in a unique way: by effectively solving a math problem – and being the only organization doing it – rather than to compete against everyone else with traditional scouting.

Whenever you can, (legally) move the goal posts such that you’re playing a different game than others – one in which you know you have an edge. But make sure you first know the rules (the ones that everyone else knows) and how to exploit them. Kurt Vonnegut wrote “If you want to break the rules of grammar, first learn the rules of grammar.” He also said “Do not use semicolons. They are transvestite hermaphrodites representing absolutely nothing.” I think he’s right; they’re worthless and sort of pretentious.

The first step in being contrarian is learning what isn’t contrarian. The uncontrarian contrarian.

R-P-S Is Life

When I play rock-paper-scissors with someone, which I try to do all the time as a way of settling disputes, paying for a bill, etc., the convo usually looks something like this:

Me: Okay, let’s just play something fair like rock-paper-scissors to see who needs to _____.

Them: Okay.

Me: Best of 21?

Them: 21!? What are you fucking crazy?

Me: Okay fine, normal best of seven then.

Them: Okay fine.

I start by offering a “fair game” in which I think I have an edge. Am I totally delusional in thinking I can win like 55% of throws against an average player? Maybe, but whatever, if you aren’t living your life to try to increase your rock-paper-scissors win rate by a single percentage point then why are you even living?

But really, rock-paper-scissors is pretty high-variance, which means the biggest advantage I can unlock – if I have any edge at all – is increasing the sample size of throws. Most people do one throw in a rock-paper-scissors match, and usually best-of-three at most. I suggest a totally absurd number of throws as an anchor so that I can easily get the best-of-seven match I want. Sticking around for potentially seven throws when I sometimes take 30 seconds to think between them might sound pretty awful, but not as awful as 21 of them.

In the Gambling Olympics (which I won not to brag), poker players Brandon Adams and Joe Ingram employed some unique tactics in an effort to beat me in rock-paper-scissors (I beat B.A. on one throw for $1k and lost 10-11 to Joey in a best-of-21). Against Adams, I suggested a practice round to get the rhythm down, which obviously wasn’t to actually “get the rhythm down” but rather to collect information, and B.A. immediately said “no.” He’s one of the top overall gamblers I know and is constantly searching for edges in life. I recommend his short book Personal Organization for Degenerates.

When I played Ingram, he stalled for like a minute after every round to throw off the rhythm of the game:

Ingram used Bales’ tactics against him, slow-playing every throw and taking long breaks so he could pace around the pool and pump himself up. He disrupted the flow of the game and made it almost impossible for Bales to develop a rhythm. On top of that, Ingram’s loud and aggressive style seemed to get under the skin of the typically stoic Bales. He maybe even got into Bales’ head by “practicing” his upcoming throws right in front of him, daring him to call his bluff.

I thought this was really smart because I tend to take as much or as little time as I want and then start the throw. Sometimes I want to go very quickly if the throws go in such a way that I have increased confidence in what my opponent will subconsciously do next, and usually people conform to my speed.

You know, I just realized I sound like a total fucking psychopath btw. At least I am aware.

——————–

So how do you quickly find an edge in a new space?

The first rule is pick the right game where you can be first. Find something with upside and little competition.

The second rule is to learn the rules. In rock-paper-scissors, my strategy of playing a different game of increasing the number of throws is only advantageous if I’m good at rock-paper-scissors; with a <50% win rate, it’d be detrimental. You can’t win the meta game if you haven’t yet mastered the basic one.

Once you know how to leverage the agreed-upon rules, the third rule is to make your own rules. First learn to beat the game, then learn to exploit opponents by looking for edges where they aren’t. As I mentioned in my last post on the following the habits of successful people, it’s not just what you know that matters, but what you know that others don’t.

Pick the right game. Optimize around the rules. Find scarce knowledge to subtly change the game in your favor.